Collaboration instead of competition is uncommon and almost extinct in 2022, at the center of late-stage capitalism. Farm Cut seeks to rectify that. While other businesses compete to have the best cannabis, the dankest ganja, the loudest buds, and to call anything else shwag, Farm Cut adopts a unique strategy by working together to cultivate the best.

Five family farms that make up Farm Cut can be located in Northern California’s fertile and conducive to outdoor growing areas. It consists of Whitethorn Valley Farm, HappyDay Farms, Emerald Spirit Botanicals, Down Om Farms, and Briceland Forest Farm. Instead of growing cannabis under artificial settings, each cooperating farm concentrates on regenerative and organic processes. The farms also provide their neighbors with fresh products from the area, which fosters a sense of community and support.

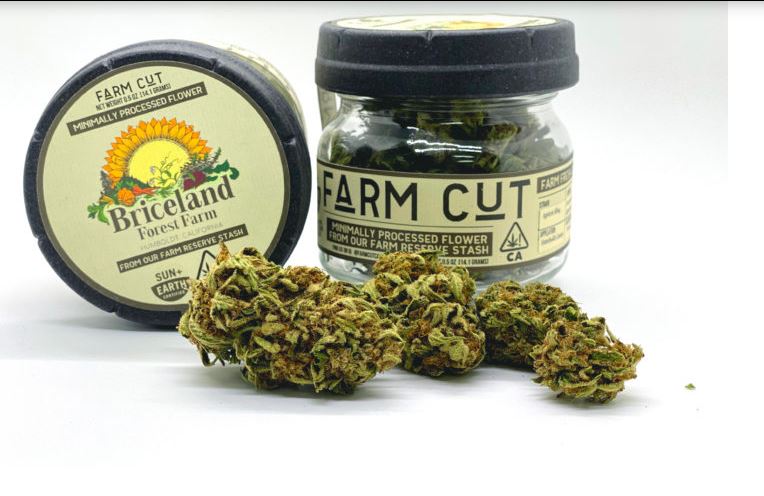

Farm Cut is unique among its competitors because they don’t trim. You did read that correctly. The little sugar leaves that cover the buds are left in place by the farmers.

The thinking behind this audacious choice is explained by Daniel Stein of Briceland Forest Farm.

He explained the method of removing the buds by running your fingers down the stems: “We actually don’t trim; Our process is that we buck it down off the stem after it’s fully dried.” After it has been bucked down, the cure takes place. When we are ready to package it, we remove any stems or larger leaves and simply brush it with gloves.

This technique produces a delicious and aromatic outdoor herb that has an added layer of weather resistance.

Depending on how it is stored, cannabis is susceptible to deterioration caused by elements like light and humidity. According to Stein, Farm Cut’s anti-trimming process keeps the plant’s terpenes and cannabinoids longer than trimming does. The small protecting leaves around the flower bud, known as the sugar leaves, are still present when the buds are presented by Farm Cut since that is how producers maintain them in their head stashes.

According to Stein, “We are trying to do this in the way that farmers preserve and keep their weed.” “When you trim it—I guess the best thing I can relate it to is, when you go to the grocery store, you wouldn’t buy a peeled banana or a peeled orange. It’s just ridiculous. They come with a natural, protective coat, and similar, that little bit of sugar leaf that’s on cannabis keeps it from hitting against other buds and moderates its moisture.”

Before rolling a joint, Stein advises cleaning the leaf matter off. After shaking the joint, throw the shake into an edible. It’s a win-win situation for everyone.

In order to preserve the quality in regards to issues like moisture retention, Farm Cut only sells quarters and half-ounces rather than grams and eighths. They overfill the reusable jars with a little extra product to make up for the leaves that inevitability makes it into the bag in order to make sure that customers are still getting what they paid for. By doing it this way, you still get a ton of ganja deliciousness, and after the leaves are taken off, there is still a ton of product.

Farm Cut emphasizes more than just paying careful attention to prolonging the life of the flower by avoiding cutting. They also comprise a close-knit group of cannabis cultivators. The collective of farms can expand the variety of items they sell to merchants by cultivating several strains simultaneously on various farms because they all stand behind each other’s goods.

According to Stein, the camaraderie between farmers is really where this brand originated. “We’re all farms that share a lot of our ethos and how and why we grow. We’ve all either met each other as friends in life or through the cannabis industry, and we’ve all had these experiences of aligning with brands that don’t really represent us. They may help us sell flowers or whatever, but they don’t represent the morals, ethos, and quality of what we want to bring into the world.”

The farms that make up the neighbourhood of Farm Cut are all privately owned. Each one serves as a homestead for families with several generations and farm animals.

This group of farmers representing the same things coming together is quite special, according to Stein. “We have vegetables, too. We’re farmers, not growers. We don’t come from the indoor growing industry. We come from a relationship with plants to the earth and feel a responsibility to take care of the earth and our community. And part of that with the food is learning to connect to the land we live on in a way that creates something higher-quality than what would be grown on an industrial farm.”